How David Ortiz Keeps Hitting Homers

On September 12, David Ortiz led off the top of the fifth inning by turning on a Matt Moore curveball, depositing it into the Tropicana Field bleachers for his second home run of the day and the 500th of his career. Ortiz became the 27th MLB hitter to reach the 500-homer milestone, and (at 39 years and 298 days) the fifth-oldest.

Ortiz didn’t get regular at bats until his age 24 season with Minnesota, and when he first came to the Red Sox, he shared the DH role with the immortal Jeremy Giambi. Contrast that with fellow Dominican and 500-homer man Albert Pujols, who had already played three full seasons by that age and collected 114 home runs as the Cardinals’ everyday left fielder. How has Ortiz managed to overcome this late start and defy the aging curve to hit dingers long after other sluggers have seen their power decline?

We can glean some extra insights from Ortiz’s relationship with Zepp’s baseball sensor. Because Ortiz is one of nine MLB players who endorse the Zepp baseball sensor, Zepp includes data and video from a couple of his swings with their app. And even when compared to the other professionals they’ve worked with, Ortiz’s swing impresses the Zepp scientists.

“Most of the athletes we work with are 25 years old, in the prime of their career,” Trevor Stocking, Zepp’s product manager for baseball and softball, said. “For him to have the kind of bat speed he does at age 38, 39, 40, it’s really special.”

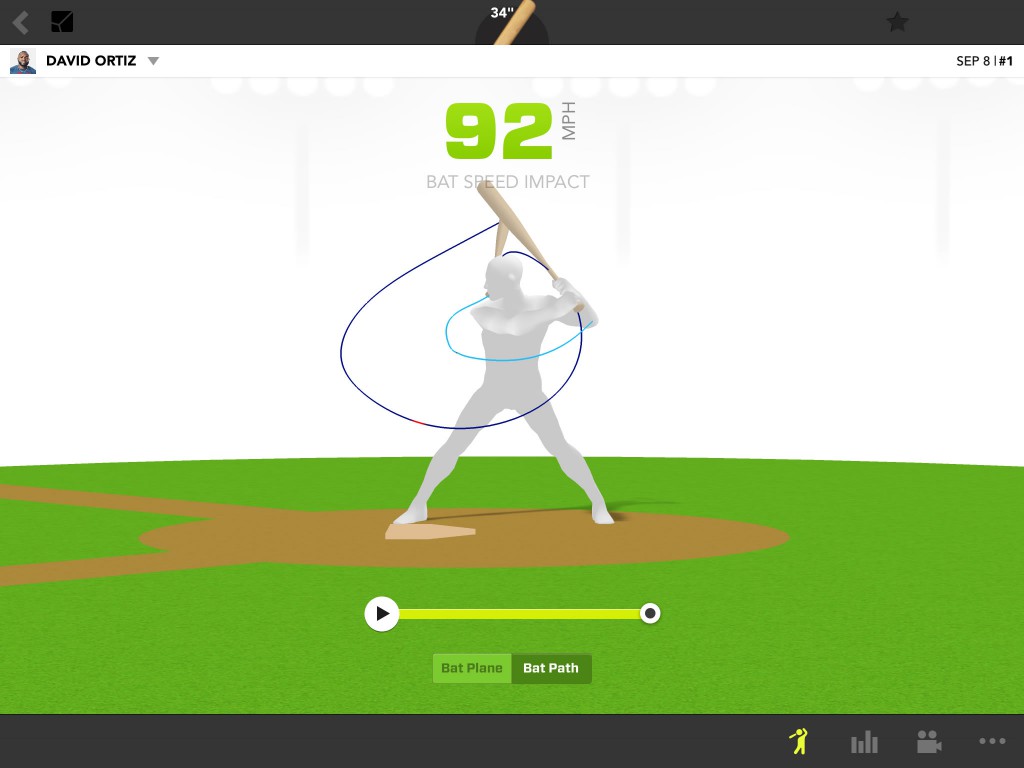

Looking at his swing data (pictured above), we see Ortiz’s swing speed is in line with other Zepp athletes like Giancarlo Stanton, Mike Trout, and Hunter Pence. Ortiz’s time to impact (how early before contact the hitter starts his swing) is just above league-average. According to Zepp, most professional hitters’ time to impact is between .14 and .18 seconds; Ortiz was clocked at .138 seconds.

Viewing his swing path in the three-dimensional representation above, we see that Ortiz focuses on keeping his hands close to his body, ensuring the bat stays on a direct path to the ball with a minimal amount of wasted energy. This helps keep his bat fast and his swing quick.

But Ortiz is a giant of a man, listed at 6’4″ and 230 pounds. For younger players who use this technology to compare their swings to that of their heroes, it might not be a great idea (or even possible) to mimic his strategy without his strength. But Stocking says there are still lessons to be learned from his data.

“What you come away with each time you work with David Ortiz is a respect for how hard he works,” Stocking said. “He understands his swing and has a plan when he gets in the batter’s box. That’s something we can all strive to do.”

Apart from Ortiz’s successes, Zepp has had a few accomplishments of their own this summer. The company inked deals with the Angels, Diamondbacks, Padres, and Rays to provide sensors and data to hitters throughout those organizations. CEO Jason Fass said the four teams are additions to Zepp’s existing stable of MLB organizations, but declined to divulge how many or which teams, citing non-disclosure agreements.

Zepp also strengthened their existing relationship with Perfect Game, providing sensors for in-game use at this summer’s showcase events like the PG All-American Classic. The in-game data from such high-level talent provided a novel database for Zepp’s research.

“It’s the first time ever this kind of data has been recorded with pro-level talent,” Stocking said.

The Perfect Game data also hinted at a relationship between attack angle (or swing plane) and success. In the admittedly small sample gathered at the showcase, the average hit was associated with a slight uppercut, an attack angle of 12 degrees. Most outs, on the other hand, were produced by a nearly flat or slightly downward swing, having an average attack angle of -2 degrees.

“This would back up a lot of our MLB data that tells us most line drives occur when the attack angle is between five and 20 degrees,” Stocking said.

The Zepp sensor is a square, neon green device held in place by a flexible strap that goes over the knob of the bat. The sensor contains two accelerometers and one gyroscope, allowing Zepp to track the bat’s path through six degrees of freedom. Having two accelerometers allows the sensor to track the large, high-frequency accelerations that happen around impact while still accurately tracking the lower-frequency accelerations as the bat moves through the zone. The sensor connects via Bluetooth to an Android or iOS phone or tablet, where swing data (and simultaneous video) can be captured, stored, and compared to friends and professionals like Ortiz, Stanton, Trout, and others.

Bryan Cole is a contributor to TechGraphs and a featured writer at Beyond the Box Score. You can follow him on Twitter at @Doctor_Bryan.

Is this a post about David Ortiz hitting dingers, or about new business Zepp has generated this year?

You switched gears about halfway through.

This is an ad for Zepp and I think that should be made clear.

I ended my boycott of TechGraphs to read this article, and for the first half I was not disappointed. “This is why TechGraphs should show up in the sidebar of FanGraphs,” I said to myself. Then it became an ad for your product. And I was betrayed.

Never again.

#KeepNotGraphs

Lots and lots of performance enhancing drugs.

Tough crowd in this comment section. I appreciated this post.